Deutsch Nicht Deutsch

Nearly ten years after packing up our lives and moving to Germany, we've embraced our adoptive country: wonderful friends, great culture exchanges, a lot of taxes, and many other things. While navigating the complex "Einbürgerung" process, we were inspired to make a multi-piece art installation exploring the absurdity, glitches, and deeper questions of national identity and citizenship.

German Not German

Deutsch / Nicht Deutsch

When we made Deutsch / Nicht Deutsch, we tried to push the limits by using publicly available AI models, enforcing a face test, and pondering 'what ifs' to explore what it would mean if the process would indeed be close to absurd and dystopian, unlike how it currently works, with the hopes that our work wouldn't trigger a denial of our citizenship application.

Physically, Deutsch / Nicht Deutsch consists of six interactive pieces, a waiting area, a certificate counter, and a large screen. Participants have to complete 4 tests in order to find out whether the system deems them German or not. Except for The Language Test, the installation is available in multiple languages.

The Ticket Dispenser

Most, if not every, office at any respectable institution must have a ticket dispenser to prove that they're capable of following one of the most important concepts of bureaucracy: order.

Instructions are uncertain, but we could consider this test number zero... Failure to understand that one needs to press a button to get a number must definitely mean one is not capable of going through any test, or?

The Face Test

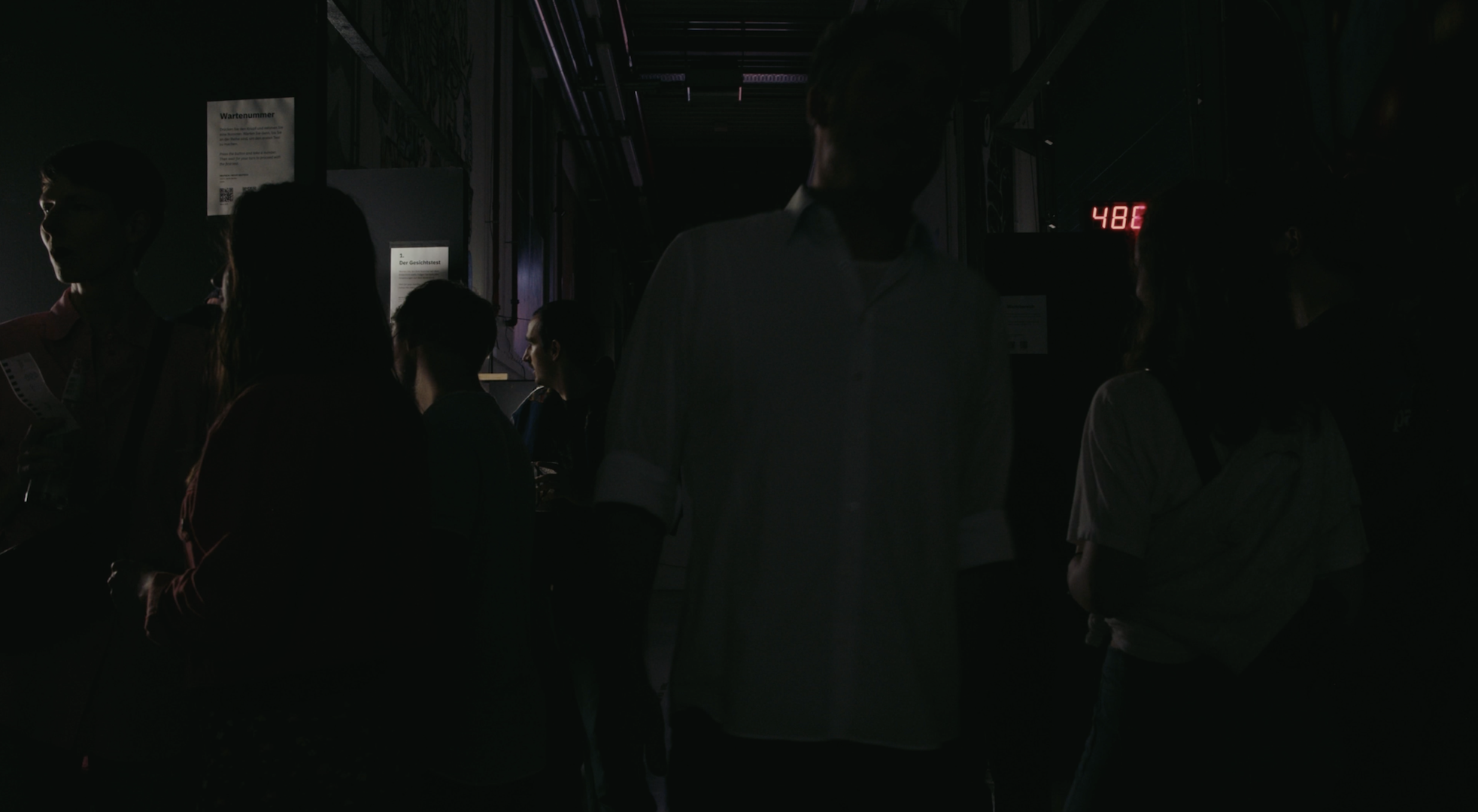

Once they see their number flashing on the panel, the candidate must rush to the first test: Der Gesichtstest.

When they press a button, a rectangle indicates the location they need to place their head on the screen.

Since the camera is at a fixed height, the participants must first find a way to either raise or lower themselves to match the camera's level. Some stretch their necks, others bend their knees or stand on tiptoe, while a few even resort to asking for makeshift platforms, only to be greeted with the phrase "Keine Fragen" by humans overseeing the process.

The candidates who fit the mold easily breeze through, barely noticing the discomfort of others. On the extremes, failure to align one’s face within the allotted time leads to an even harsher consequence: a new number, a new wait, and the whole process begins again.

Once the test is complete, the machine answers:

"Deutsch" or "Danke", and invites the candidate to go to the next test.

The Knowledge Test

Der Wissenstest is, in fact, a distilled version of the actual citizenship test one needs to pass in order to become a German citizen.

Our version is a series of 3 questions, randomly selected out of a total of 310, that the participants must answer in 30 seconds, or less.

The candidates must have at least a broad understanding of German history, culture and simple things, such as women's right to vote to choose their own partners. And even surprising legal norms, like the prohibition against a man having two wives at the same time...

The real obstacle isn't always knowledge. It's understanding the instructions, a detail that some candidates overlook. Nervous fingers might twitch, hover, or hesitate over the keys, misinterpreting the format or the phrasing. Others might forget to confirm their answers or fail to submit in time.

The Language Test

Similar in shape and form to the previous test, Der Sprachtest aims to assess the candidate's grasp of German grammar and vocabulary.

It presents a series of single-choice items that appear straightforward on the surface. However, they are not random—they are tailored to the candidate’s profile.

After analyzing the person using the previous tests, the system calibrates the vocabulary, sentence structures, and even the images that accompany the tasks. This creates a situation where the participant is often forced to choose between grammatically correct but uncomfortable descriptions of themselves and grammatically incorrect yet more comfortable ones, all under the pressure of time.

The Phone Interview

But how reliable is any testing without an oral exam?

Once all other tests have been completed, the candidate is asked to wait in front of a phone, which will ring and produce a tailor-made question, spoken by a casual, yet precise machine-voice.

On Das Telefoninterview, the topics may range from everyday situations, such as asking for directions or discussing work, to abstract concepts like personal goals or opinions on societal issues. It may also be something as complex as "What role should Germany play on the global stage?" or as simple as "How long until you shave that beard?".

But the real test lies in responding coherently, with correct grammar, while maintaining the rhythm of a natural conversation.

As a matter of fact, ignore the last sentence: it is impossible for us to know what would make the machine pass or fail the candidate at this point. What we know is that it listens, processes, and then abruptly ends the call.

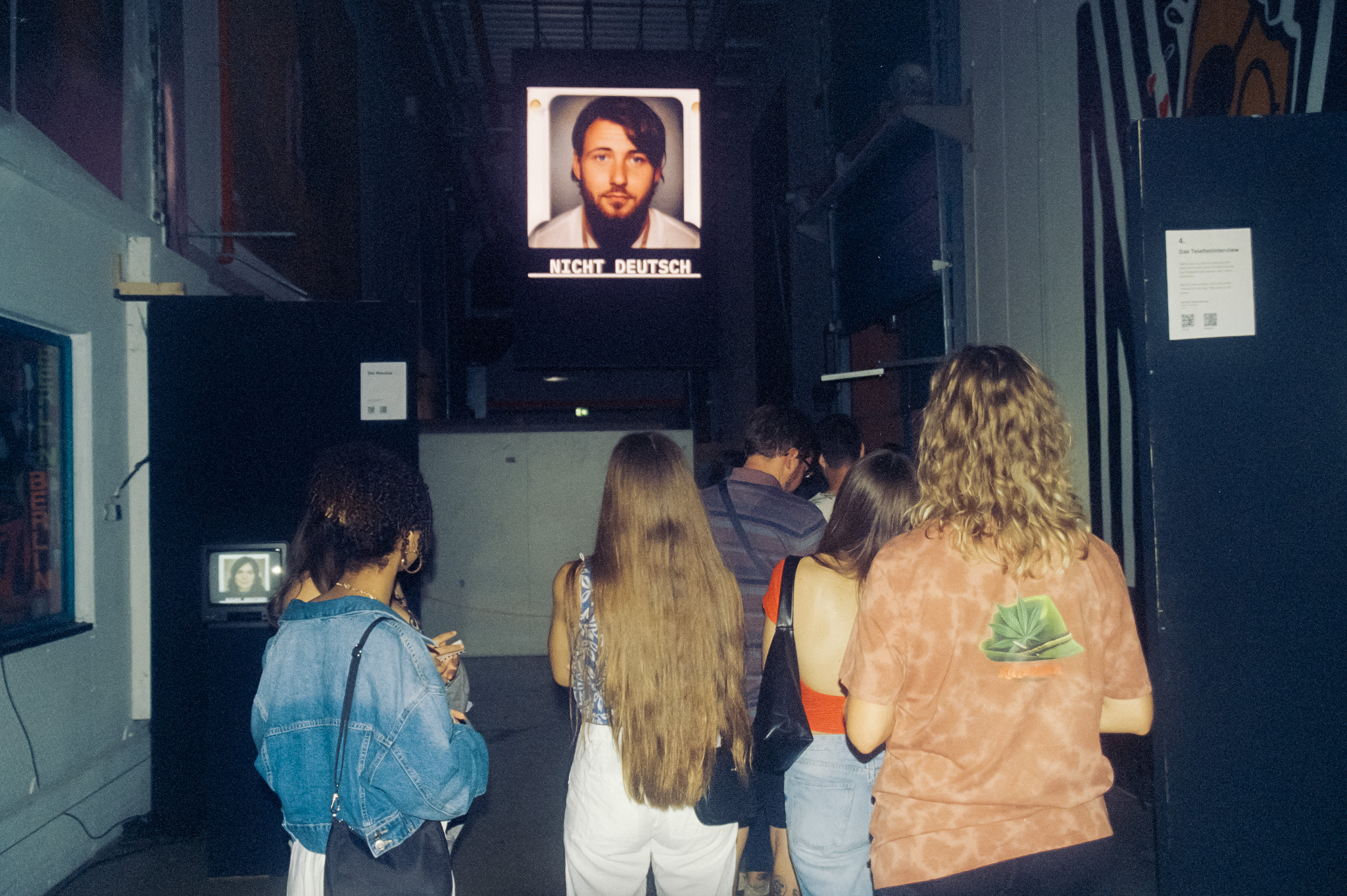

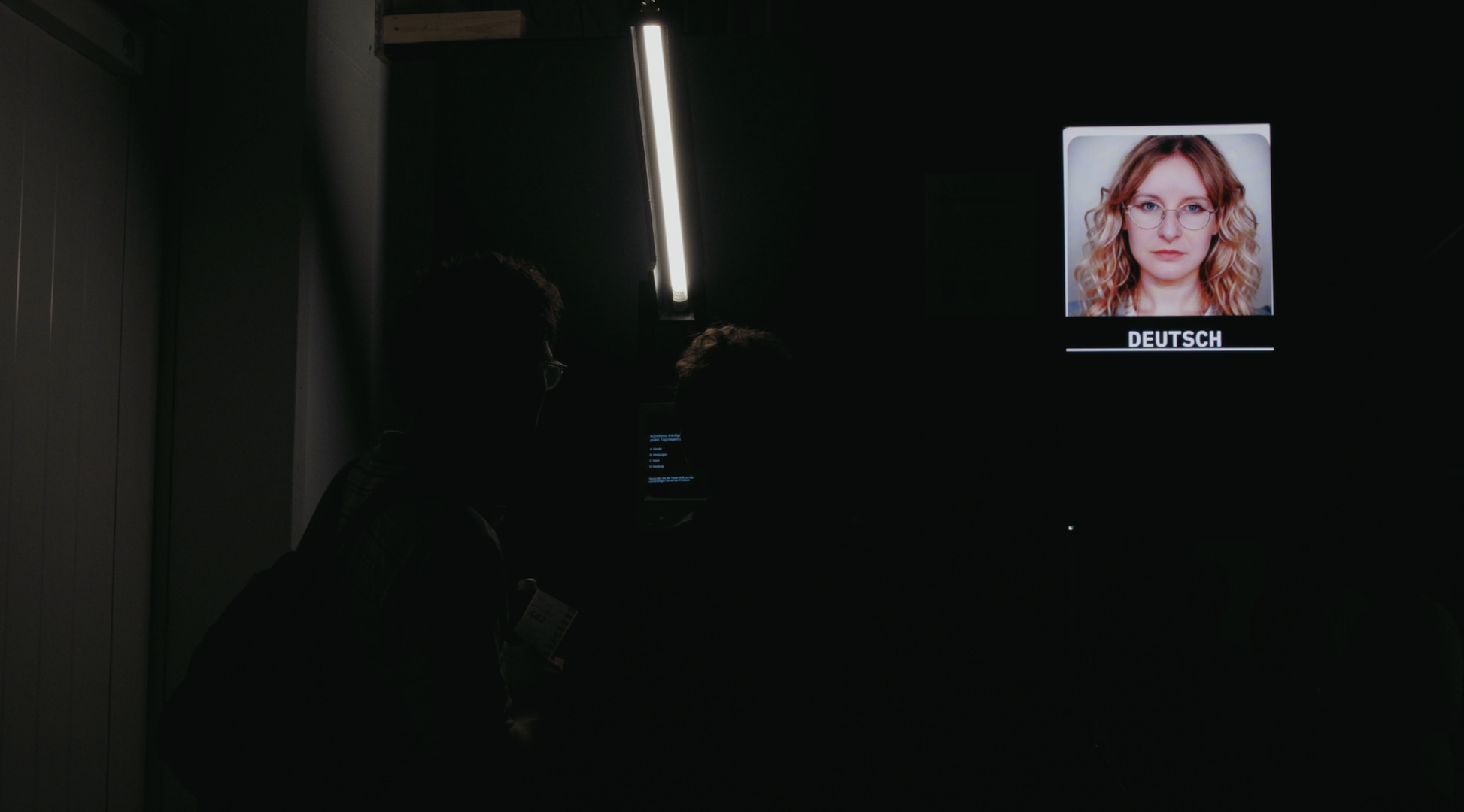

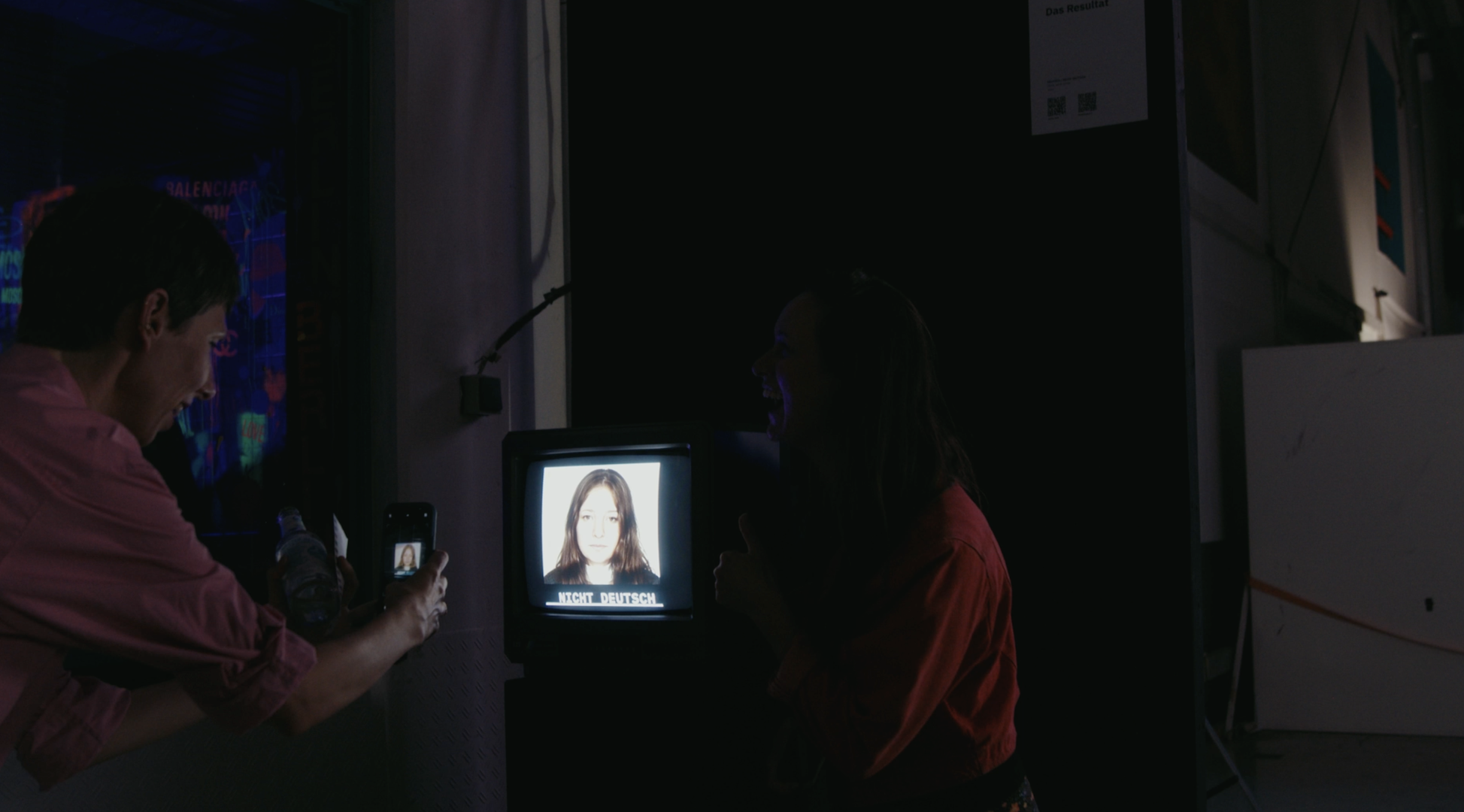

The Results

Once the process is over, the participants receive their results in the most public manner possible.

One by one, their portraits—digital interpretations of their faces, stripped of nuance—flash onto a CRT monitor and massive screens spread around the room. The machine, having processed each candidate’s responses, now delivers its final judgment with an unfeeling certainty.

There is no fanfare, no explanation—just a single label beneath each image: “DEUTSCH” or “NICHT DEUTSCH.”

Bureaucracy at its finest, yet, satisfaction not guaranteed...

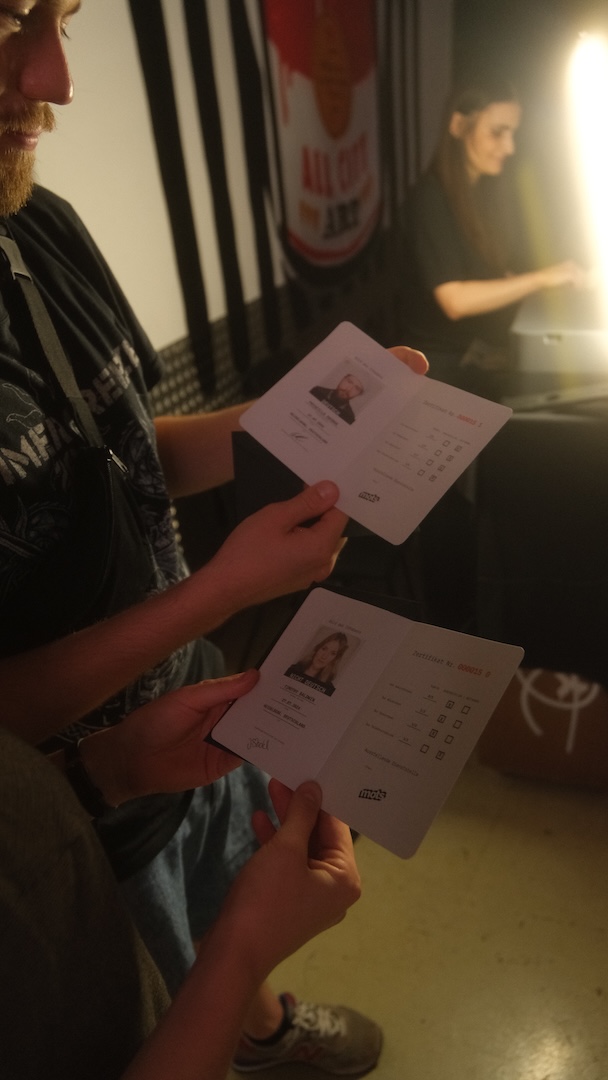

The Certificate

At the end, participants are offered printed and authenticated certificates with their photo that they have to sign, perhaps just as a hollow symbol of accomplishment but more so as proof that they were willing to have their identities reduced to nothing more than a process to which they willingly complied.

For some, the certificate stands as a formal recognition of their ability to conform, their success in navigating the system's rigid expectations, regardless of whether they passed or failed.

For others, the certificate is a confirmation of their failure, a reminder that they have not fitted the mold the machine deems worthy. The same stamp, the same emboss, but with a different verdict—a neat, bureaucratic determination of how much or how little they belong.

Whether they enjoy being called Deutsch or Nicht Deutsch is something each candidate has to decide for themself.

Photo dump